Training The Utilization Limited Athlete

A Comprehensive Guide to Training Interventions & Tools

This article is a companion piece to my previous articles titled, Training The Delivery Limited Athlete and Training The Respiratory Limited Athlete.

Before discussing training interventions for utilization limited athletes it’s important to acknowledge that the underlying causes of utilization limitations are quite broad, and as a result we cannot have once catch all set of foundational components that need to be addressed for these individuals. For example, a lack of mitochondrial density, a disruption to the normal muscle fiber structure, changes in intramuscular and intermuscular coordination after injury, chronic overtraining, and a left shift in the hemoglobin dissociation curve from hypocapnic breathing can all impair skeletal muscle oxygen extraction. In order to reconcile this, I suggest we zoom in on mitochondrial density as that will have a meaningful impact on both the magnitude of oxygen extraction, as well as the rate. Additionally, that falls within the sphere of influence of coaches, whereas some of the other contributing factors for utilization limitations are less easily assessed and influenced without bringing other trained professionals into the fold.

What I find interesting about training utilization limited athletes is how tightly changes in their physiology are linked to improvements in performance. Assuming a utilization limited athlete is not overtrained or injured, the primary adaptations they’ll want to target in their training are increased mitochondrial density, increased enzyme concentrations, improved coordination and recruitment, and increased metabolic oxygen utilization. With a quick internet search, you can look up any of these key terms and find a host of protocols that claim to improve mitochondrial biogenesis. However, I’m always skeptical when I see cookie cutter protocols and programs that claim to elicit a highly specific adaptation without any instruction for how to adapt the program to the individual or any inbuilt autoregulatory components.

There are plenty of protocols that should elicit a given adaptation in theory. They may even consistently improve performance. However, we don’t always have a reliable way of knowing how and why they lead to performance improvements. As a coach, or athlete, you may not even care why something works (as long as it does work), but there’s a good argument to be made for why you should care.At some point, you’re bound to encounter an athlete who doesn’t respond to cookie-cutter protocols. If you don't understand the underlying impacts of your training methods and how they relate to improvements in performance you may not have the means to modify their program to allow for continued progress.

In figure I, we have ΔSmO2 and maximum power output data from a Crossfit athlete over 36 weeks of training. ΔSmO2 is a measurement of the rate of change of muscle oxygen saturation, which represents the balance of oxygen supply and utilization in the working muscle. The more negative ΔSmO2 becomes, the greater an individual's maximal rate of oxygen extraction. When I first encountered this athlete we identified that their rate of oxygen utilization was their primary limiting factor for increasing their VO2max and maximal power output. In testing we found that this individuals maximum rate of oxygen extraction was 4.5% MO2 per second and that their maximum sprint speed on the echo bike was ~1,315 watts. Over 36 weeks of training I had this athlete establish a max power output on the Echo Bike and then complete an auto-regulated repeat desaturation workout at 75% of their daily maximum power output. In figure I we have the highest power output they hit each week as well as the three most negative ΔSmO2 values they recorded.

Over these 36 weeks we observed a 20% increase in their maximal power output and a 31% increase in their maximum rate of oxygen extraction. When we calculated the correlation between their ΔSmO2 and maximum power over time the R² value was -0.95, which indicates a near linear relationship between improved oxygen extraction and increased power output. Said differently, as we increased this athlete's maximal rate of oxygen utilization there was a proportional increase in maximal power. Furthermore, when we calculate the R² between their week to week training progress on the weekly repeated workout and their increase in power output the R² value was +0.84. Collectively this gives us a strong understanding of how the procol we used works, how it changed the athletes physiology, and how this relates to increased performance.

In another instance I had an athlete who wanted to improve their performance on a 30-second Echo Bike for max calories. After assessing this athlete we determined that they need to improve their maximal power output to get better at this test since they were holding a very high percentage of their maximal sprint speed already. Additionally, we found this athlete was limited by their rate of oxygen utilization. Over a ten week period we had this athlete complete one developmental U2 training session as well as a 30-second Echo Bike test. In figure II you'll find their five most negative ΔSmO2 values captured during their U2 training sessions plotted against their performance on the 30-second Echo Bike test. Over the ten week training period they consistently hit more negative ΔSmO2 values, and they also improve their score on the Echo Bike test nearly every week. When calculating the R² between ΔSmO2 and performance, I got a value of -0.97. This tells me that the training intervention not only yielded the correct physiological outcome, which is an increase in the rate of maximal oxygen extraction, but also that this physiologic change drove the desired performance outcome.

Tier One Energy System Training Interventions:

In this section I'm going to discuss the tier one energy system training interventions for utilization limited athletes, which include U1 and U2 training respectively. Traditionally these two training categories would be referred to as ‘anaerobic lactic endurance’ training and ‘alactic power’ training, though it should be understood that these terms are misnomers given that oxygen and lactate are both part of the energy transduction process at all times. U1 and U2 training can both be used to increase one’s magnitude and rate of oxygen utilization in the skeletal muscle which we can juxtapose to the basic delivery training categories, D1 to D3, that improve one’s rate of oxygen delivery. Consequently, U1 and U2 training are referred to as deoxygenating training.

U1 training has traditionally been referred to as lactic endurance training in Crossfit, anaerobic power endurance training in strength and conditioning circles, or purple training in swimming. If you have ever done this type of training the purple designation will make intuitive sense as that is the color you’d expect your face to be after completing a U1 training session. The target adaptations for U1 training are improved tolerance to high levels of acidosis, increased intramuscular and systemic buffering capacity, and an extension of the amount of time one can operate with lowered muscle oxygen saturation levels. Examples of athletes who may benefit from this type of training are elite Crossfit competitors preparing for a sanctional event, one hundred to two hundred meter swimmers who need to be able to preserve a high percentage of their max sprint speed for an extended duration, or elite eight hundred meter runners. My general guidelines for performing U1 training are as follows:

U1 training is best completed in an interval format using forty second to one hundred eight second long intervals and resting between three and twelve minutes between work intervals. However, U1 training can also be performed in a continuous format with a single work bout lasting between three and fifteen minutes. It should be noted that athletes with poor delivery may not tolerate this style of work and will need longer than average rest periods between sets whereas athletes who lack absolute power will get a subpar stimulus from this style of training.

U1 training should be performed at a maximal or near maximal exertion level. This style of training is exceptionally difficult and athletes will often develop a fear or distaste for this style of training. For individuals recording biometric data we should expect to see heart rate values between ~95-100% of an individual's maximum heart rate, moderate to high blood lactate level, and muscle oxygen saturation levels that are rapidly declining or stabilized between roughly 5 to twenty percent. For those without biometric data, U1 training should be done at ~95-100% effort and if asked an athlete should only be able to speak in one to three word sentences before it disrupts their sense of composure.

U1 training poses the greatest recovery demand compared to all of the other tier one energy system training categories. As a result, it’s recommended that this style of training is not performed more than once per week, and that it is not performed for more than three to six consecutive weeks.

Cyclical modalities are most effective when performing U1 training sessions. However, most global movements can elicit an appropriate training response assuming a near maximal cycle speed can be maintained and power output stays relatively high. Regional and local movements for U1 training due to the fact that they do not elicit a great enough whole body energy demand.

Example U1 Sessions:

The most important things to keep in mind when prescribing U1 training sessions are as follows:

This style of training is exceptionally stressful to athletes, both mentally and physically. As a result, it should be used sparingly in an athletes training program, if used at all. For most athletes I would advise against performing more than one U1 training session per week, and I would limit a progressive structure to 3-4 weeks in most cases.

Rest intervals should provide ample recovery so that an individual can maintain similar power outputs across repeats. If training quality begins to deteriorate it’s recommended that the rest duration is extended, or that the session is terminated early.

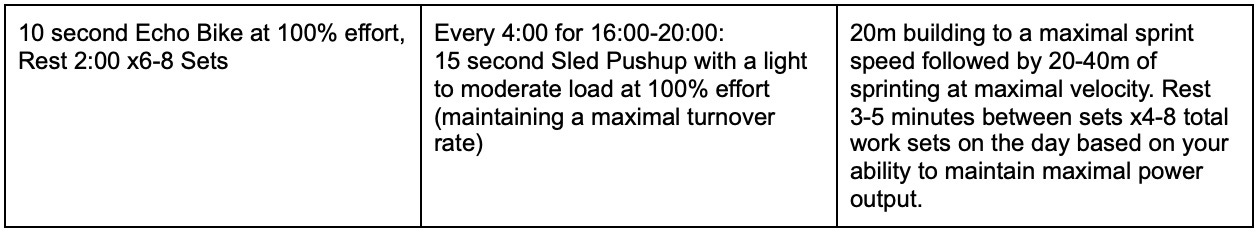

The final tier one energy system training category is U2, which is traditionally referred to as ‘alactic power’ training. It should be noted that this term is a misnomer, because lactate is certainly generated while performing this style of training. However, it tends to be consumed at a relatively fast rate as well, which is why measured blood lactate concentrations will appear low when performing this style of work. The target adaptations for U2 training are an increased rate of oxygen utilization, increased recruitment of fast twitch muscle fibers, increased mitochondrial density, and increased maximal power output. Examples of athletes who can benefit from this style of training are Crossfit competitors who are enduring, but lack absolute power, two hundred meter runners who need to improve their top end speed, or field speed athletes who have to cover short distances in the fastest possible amount of time. As far as training guides go, U2 training is best done within the following constraints:

Very short work bouts lasting between five to twenty seconds with long, complete, rest periods between sets.

U2 training should be performed at a maximal intensity. While this style of training is hard, the short time durations and extended rest periods make it quite tolerable for most individuals. For those monitoring biometric data, muscle oxygen saturation levels should reach personal minimum thresholds when performing this style of work. Heart rate is not an applicable metric during this style of training, and while high levels of lactate are produced during this style of work the complete rest periods allow for clearance rates to exceed production. Thus, making blood lactate measurements an ineffective monitoring technique for this style of training.

Most individuals need forty eight hours or more to recover from U2 training, though some advanced athletes may require a longer period of time between training sessions.

U2 training is best done with specific cyclical modalities including running, sled pushing, and cycling.

Example U2 Sessions:

The most important considerations when performing U2 training are two fold:

Most athletes will feel the urge to cut their rest intervals down during this style of training. However, they should resist the urge to do so since this form of training requires maximal intensity on every work set, without degradation from set to set.

Volume does not need to be high to get the desired training effect from U2 training. Advanced athletes can often make improvements with no more than three to four sets per week.

Tier Two Energy System Training Interventions:

Imagine we take an elite cyclist and have her do a step test on a stationary bike with a muscle oxygen saturation monitor affixed to her vastus lateralis or rectus femoris. We would see that she has a well developed cardiovascular system, and subsequently a great ability to deliver oxygen to her working muscles. Given her extensive training history on the bike it’s also likely that she excels at utilizing oxygen in the working muscles while performing her sport. Now imagine we take this same athlete and we have her perform a step test on a Skierg with a muscle oxygen saturation monitor on her triceps and lat. It’s likely that she will still present with good oxygen delivery to the working muscles, but i’d suspect that her oxygen utilization would be impaired. The reason for this is that she lacks mitochondrial density in the extremity muscles of the upper body. One way to improve this would be to have her perform repeat desaturation training on a skierg. This method of training needs to be performed at a near maximal intensity with an interval duration that is long enough for muscle oxygen saturation to reach a nadir. So far as repetitions, we want this individual to keep going until she can no longer deoxygenate the muscle down to the same nadir as previous sets or she cannot recover muscle oxygen saturation back to the same baseline level. In the session examples below you’ll find a NIRS guided, auto-regulated, and mixed repeat desaturation training session.

Example Repeat Desaturation Training:

Before wrapping up this chapter on training utilization limited athletes I wanted to expose a common misconception, which is that we only need to train an individual's limiter to increase their performance. For example, only training to improve a utilization limited athlete’s rate of oxygen utilization and ignoring all else. This is a mistake in my opinion. Just because you’re limited by utilization in the vast majority of sport specific contexts does not mean that you cannot be limited by your cardiopulmonary system, and oxygen supply, in other scenarios. You do not fail in an event when your ‘limiter’ cannot cope with the imposed demand. You fail when you’ve exhausted all forms of compensation. Improving your limiter gets you further before you begin to rely on those compensation patterns, but you still need to improve those other systems, for lack of a better term, as they will be pushed to their capacity eventually. While it’s important to train known limitations and grab the ‘lowest hanging fruit’ that doesn’t mean that there is not a time and place to climb a higher higher and grab some fruit from the top of the tree.

If you enjoyed this article you may enjoy the following articles as well:

As always, if you enjoyed this article please share it with a friend. Additionally, if there are specific topics you’d like to see my write about in the upcoming week you can shoot me an email at EvanPeikon@gmail.com